The Bow Street Players involved in a famous murder and ghost story

By Jon Short

In our previous blogs, we have seen that the majority of detainees held overnight in the Police cells resulted from activity around anti-social behaviour. Nonetheless, the station did occasionally deal with more notorious crimes and this included the major news event of December 1897 following the murder of the famous actor William Terriss by Richard Prince.

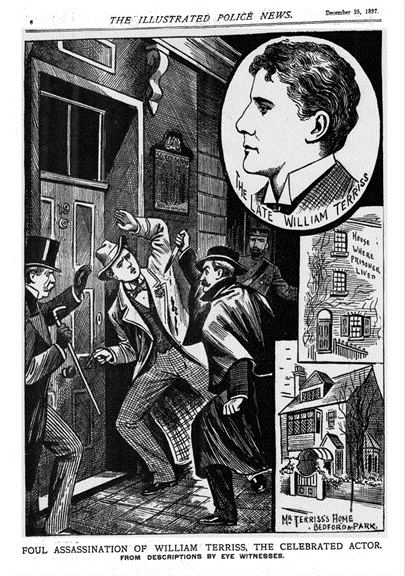

On the evening of Thursday 16th December 1897 Constable John Bragg (272E) was on point duty, directing the traffic, at the junction of Strand and Bedford Street a short distance from the front entrance to the Adelphi Theatre.

Shortly before 7:30pm he heard cries of “murder” and “police” from the vicinity of the rear of the theatre in Maiden Lane. On arriving at the scene Bragg did not see a victim but encountered Richard Archer Prince who had made little attempt to flee and had been restrained among a small number of bystanders including Henry Graves.

Graves informed the PC that he had accompanied his close friend William Terriss to the Adelphi and witnessed Prince stabbing him. Bragg, Graves and Prince walked to Bow Street arriving around 7:45 pm and Prince was booked into custody by Inspector George Wood.

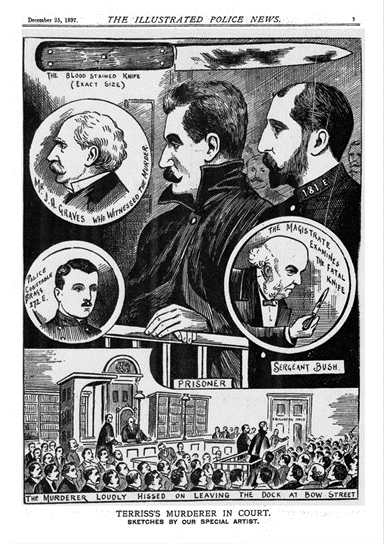

Prince confirmed Graves’ accusation and handed over the blood-stained butcher’s knife that had been used in the attack.

Wood searched Prince, collecting a number of letters and 5 tickets for clothing that had been pawned, and took him to an area referred to as the Sergeant’s Room attached to the Charge Room.

Inspector William French took the witness statement from Henry Graves who had dined with Terriss and his companion, actress Jessie Millward, at their flat in Prince’s Street Hanover Square and at 7 pm the pair had taken a cab to the private entrance to the Adelphi in Maiden Lane; Millward having left for the same location a little earlier. At the door, Graves saw Prince rush and strike Terriss on the back, at first believing it to be an over-aggressive friendly slap, but realised the truth as another blow was landed.

French and Graves made their way to Maiden Lane and both were present at the doorway when the doctors who had been called from Charing Cross Hospital pronounced the victim’s death just before 8:00 pm

French returned to Bow Street and at 9:45 pm Prince was informed that he would now be charged with murder.

Inspector William Croston took over from Inspector Wood at 10 pm[1], and was asked by Prince to make contact with his sister. Wood sent the telegraph and later received and gave the response to the prisoner that she wished to have nothing further to do with him.

Both Wood and Croston noted that although tense, Prince remained quite calm and softly spoken at all times.

Inspector Alfred Leach was dispatched first to the Adelphi theatre but found nothing incriminating in Terriss’ belongings there. He then travelled to Prince’s lodgings at Eaton Court, Eaton Square and recovered a number of documents including a list of subscribers to the Actors Benevolent Fund, William Terriss being one of the named benefactors.

In the Magistrates court the next day under the stewardship of the Gaoler, Sergeant Bush (181E) the usual selection of prisoners were brought before Magistrate Sir John Bridge on charges of drunkenness, begging, theft and one of malicious wounding before Prince appeared and was charged: “For he did about 7:20 pm on 16th December 1897 kill and slay one William Terriss with a knife”.[2]

The witness statements were given and Prince was remanded to Holloway Prison pending the outcome of the inquest that was held at St Martin’s Town Hall the following Monday; the body having been taken to the crypt at St Martins in the Fields.[3]

With the inquest confirming the death as a wilful murder Prince appeared at Bow Street before John Bridge on Wednesday 22nd December and again seven days later.[4] The original statements were reaffirmed with further information being gathered by Inspector Leach and doctors requested to assess Prince’s mental state.

The charge was committed to trial at the Old Bailey and was heard on Thursday 13th January 1898. Once again the police statements were given as before along with additional statements from the stage doorkeeper and Terriss’ dresser. For the defence, evidence was given by Prince’s mother, a number of theatrical agents and, of most significance, a number of physicians including Dr Teophilus Bulkely Hyslop an eminent specialist in mental health who opined that Prince was delusional. The jury was sent out at 6:30 pm and after half an hour of deliberation returned a verdict of guilty but accepted that although Prince knew what he was doing and to whom, he was not responsible for his actions due to insanity. Instead of being hanged, he was ordered to be detained at Her Majesty’s pleasure.[5]

It may not have been the most challenging case for the Bow Street Officers but was a major event. The court was packed on each occasion Prince appeared and the news reported around the world as “Breezy Bill” Terriss was so well known,[6] and there are plenty of online resources that provide greater detail.

The notoriety was such that on Boxing Day Madame Tussaud’s Exhibition had a portrait model of Terriss on display,[7] and this was followed by another of Prince within a few days of the trial.[8]

Terriss was the stage name of William Charles James Lewin, born in 1847 the son of a barrister, and in between dabbling with acting, had attempted various business ventures around the world including tea planting, sheep farming and horse breeding. Eventually, in the late 1870s he settled on acting and became very successful and popular, taking lead roles at Drury Lane, The Adelphi and the Lyceum and touring the USA.[9]

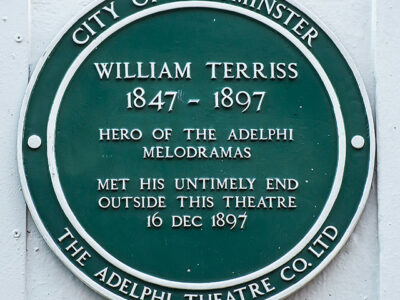

In 1894 he returned to the Adelphi company to be the regular lead in their production of melodramas, and his status gave him use of a private entrance in Maiden Lane, not the stage door in Bull Inn Court. In December 1897 he was playing the role of an American Civil War General in the play “Secret Service”.

His funeral was held on Tuesday 21st December 1897,[10] and up to 50,000 people lined the route or filled the cemetery as the procession made its way from the family home at Bedford Park, Chiswick to Brompton Cemetery.[11] Queen Victoria sent condolences and a wreath of orchids and lilies was received from the Prince of Wales.[12]

Richard Archer Prince was born Richard Archer in 1858 in Dundee. He had gained occasional acting work as a Super (essentially non-speaking roles without mention on the playbill) but considered his talents to be far superior.

Struggling for regular income he would intermittently return to Dundee and work as a labourer, but back in London by late 1897 theatre roles were still not forthcoming. As a result, Prince was forced to pawn clothing and apply to the Actors Benevolent Fund for assistance. The charity did provide him with a number of grants totalling £3 but turned down a request on the day of the murder.

He held grudges against a number of leading actors and stage managers for his inability to find work but Terriss in particular, even though the latter was a contributor to the Benevolent Fund and had written a positive reference to assist Prince’s attempts to find roles.

Following the verdict Prince was transferred from Holloway to the Broadmoor Lunatic Asylum, as it was then known, where he died in 1937.[13]

But the story does not quite end there.[14] Actors have reported strange tapping sounds in the Adelphi’s dressing rooms; there have been reported sightings of a man “gliding” through Maiden Lane; London Underground staff and electrical workers have provided numerous reports of a man walking through Covent Garden station after shutdown, and, though the tube station was not completed until 1907, it occupies the site of a popular bakery at the turn of the century.[15]

In 2012 the comedian, actor and TV personality Jason Manford was playing at the Adelphi and during a video call his daughter asked who was the sad-looking man dressed as a soldier in the room.[16]

These supernatural events have all occurred in areas closely linked to the life of William Terriss and are attributed to his ghost. This scribbler does not believe in the existence of ghosts but, according to a 2017 survey, 1 in 3 people in the UK do[17]. Psychologists have attempted to explain why this may be the case[18] and there is an abundance of paranormal activity in the Covent Garden area to explore.[19]

Additional References:

William Terriss & Richard Prince: Two Characters in an Adelphi Melodrama; George Rowell, 1987; ISBN 978-0854300426

The Battered Body Beneath the Flagstones and Other Victorian Scandals; Michelle Morgan: 2018; ISBN 978-1472139474

[1] https://www.newspapers.com The Birmingham Daily Post, 23 Dec 1897 [18/07/2023]

[2] London Metropolitan Archives; Bow Street Magistrates Court, Court Registers, Reference: PS/BOW/A/01/005

[3] https://www.newspapers.com The Evening Standard, 17 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

[4] https://www.newspapers.com The Guardian, 21 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

[5] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 31 May 2023), January 1898, trial of RICHARD ARTHUR PRINCE (32) (t18980110-113).

[6] https://www.newspapers.com The New York Times, Fri 17 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

The Chicago Chronicle, Fri 17 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

The San Francisco Examiner, Fri 17 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

The Ottawa Daily Citizen, Fri 17 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

The Sydney Morning Herald, Sat 18 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

The Age Melbourne, Sat 18 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

[7] https://www.newspapers.com The Pall Mall Gazette, Mon 27 Dec 1897 [23/03/2023]

[8] https://www.newspapers.com The Weekly Dispatch, Sun 30 Jan 1898 [09/05/2023]

[9] https://www.newspapers.com The Guardian, 22 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

[10] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; Office of Works and successors: Royal Parks and Pleasure Gardens: Brompton Cemetery Records; Series Number: Work 97; Piece Number: 178

[11]https://www.royalparks.org.uk/parks/brompton-cemetery/explore-brompton-cemetery/famous-graves-and-burials/william-terriss [28/05/2023]

[12] https://www.newspapers.com Evening Standard 21 Dec 1897 [10/02/2023]

[13] Daily Mirror; Publication Date: 27 Jan 1937

[14] London Guided Walks Podcasts Episode 69 https://londonguidedwalks.co.uk/podcast/victorian-actor-william-terriss/ [28/05/2023]

[15] British Library Untold Lives 31 Oct 2017 https://blogs.bl.uk/untoldlives/2017/10/the-ghost-of-william-terriss.html [21/05/2023]

[16] BBC Sounds 21 Jul 2022 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ObDFY_z3Aqo [21/03/2023]

[17] YouGov 2017; https://yougov.co.uk/topics/politics/articles-reports/2014/10/31/ghosts-exist-say-1-3-brits [24/07/2023]

[18] https://www.psychologytoday.com/gb/blog/out-the-ooze/202110/why-some-people-see-ghosts-while-others-never-do [24/07/2023]

[19] https://www.paranormaldatabase.com/hotspots/WC2.php [24/07/2023]