The cause and effect of poverty and crime is much debated even today, and treating vagrancy and begging as criminal acts only increases the problem. Many Londoners faced this vicious cycle and from our census research we have a brief biography of one such person.

Written by Jon Short

An incorrigible rogue is an expression and label that may conjure up an image of an impish or mischievous character that might also be considered a bounder or cad.

The reality, though, is much more mundane and simply defines someone that has previous convictions, mainly for vagrancy.

The early definitions of vagrancy date back to the 18th century,[1] though the most significant law is the 1824 Vagrancy Act that provides a wide ranging definition of what constitutes an Idle or Disorderly person.[2]

Predominantly this meant beggars, unlicensed hawkers and anyone “not giving a good account of himself or herself”.

As we have seen from the census records, the Bow Street Police Station cells housed numerous detainees charged with begging and drunkenness and many would have been repeat offenders and as such eventually fallen into the classification of Incorrigible.

One such example is Frank Prudames who was recorded as being held in the cells on the night of the 1901 census and was sentenced the following day at the Magistrates Court to 14 days hard labour for begging,[3] and his journey to Incorrigible Rogue is probably very similar to many of the impoverished Londoners at that time.

Frank was born in 1861 in St Pancras to Ann and James, a journeyman poulterer.[4] The family lived around Holborn and Clerkenwell and the workhouse may not have been unfamiliar. Ann, James, Frank and two other children were in Broad Street workhouse for a spell in 1869,[5] and both Ann and James ended their lives at The Holborn Union workhouse in Mitcham in 1894 and 1896 respectively.[6] & [7]

For 12 years between 1883 and 1895 Frank served with the Devon Regiment, travelling to India, and picking up a couple of convictions for breaking out of barracks and drunkenness.[8]

Outside of the army service, classified as a general labourer, he drifted around London, with occasional workhouse stays and a number of brushes with the law; indeed he was recorded on the 1881 census in Holloway Prison,[9] though the nature of the offence is unknown.

His first appearance at Bow Street was at the age of 14 and he was convicted of Larceny and Receiving at the North London Sessions and sent to the Industrial School at Feltham – a reform institution and forerunner of the Feltham YOI – for 2 years.[10]

There were further charges for Larceny; one not guilty verdict being returned as the theft was deemed to be a prank[11], but another resulted in a 1 month sentence, and identified that he also used the aliases of Frank Trujames and Frank Prudans.[12]

Alongside these there were numerous arrests for vagrancy and further appearances via Bow Street including,

- March 1900 being a rogue and vagabond – sentenced to 3 months imprisonment with hard labour.[13]

- 31 March 1901, the census day, held in the police cell after being arrested by PC Rowe 467 at 11:25pm;[14] convicted the following morning at the Magistrates Court and sentenced to 14 days imprisonment with hard labour.[15]

- April 1901, once again arrested for begging and sent to trial at the North London Sessions on 7th May receiving 8 months with hard labour in Wormwood Scrubs for being the aforesaid incorrigible rogue.[16]

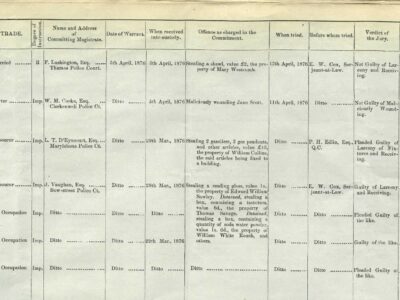

HO 140/210

Due to the reliance on the Civil Parish for poverty assistance, many vagrants and petty criminals remained within their local environs.

Interestingly, Frank did appear to buck this trend, alas without a happy ending. With a spell in Plympton St Mary workhouse in Devon in late 1902,[17] serving 7 days in for begging in Gloucester Gaol in 1903,[18] he died in 1904 in the South Stoneham workhouse just outside Southampton in between another workhouse stay in City Road.[19] [20]

Over the course of the 20th century the number of prosecutions for being an Incorrigible Rogue diminished and the statute was finally removed in December 2013.[21]

Despite multiple revisions, the 1824 Vagrancy Act, which was first introduced after the Napoleonic war to clear camps of discharged army and navy personnel,[22] is still effective and in 2021/22 over 1,100 people have been arrested in England & Wales under this act.

Following a long campaign led by Crisis, the charity organisation that offers support to the homeless, the repeal of the law was passed in just Spring 2022 but its implementation date has yet to be announced.[23] The argument as to whether being poor or homeless should be considered criminal continues.

[1] https://www.londonlives.org/static/Vagrancy.jsp [18/11/2022]

[2] https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Geo4/5/83/section/5 [07/11/2022]

[3] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/7814 [02/12/2022] The National Archives; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1901

[4] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/1558 [01/12/2022] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Church of England Parish Registers; Reference Number: P90/PAN1/035

[5] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60391 [01/12/2022] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Workhouse Admissions & Discharge Registers; Reference Number: HOBG/535/01

[6] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60391 [02/12/2022] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Workhouse Admission & Discharge Registers; Reference Number: HOBG/542/20

[7] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60391 [02/12/2022] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Workhouse Admissions & Discharge Registers; Reference Number: HOBG/542/18

[8] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; Royal Hospital Chelsea: Soldiers Service Documents; Reference Number: WO 97

[9] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/7572 [01/12/2022] The National Archives; Census Returns of England and Wales, 1881

[10] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/61808 [01/12/2022] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 140 Home Office: Calendar of Prisoners; Reference: HO 140/35

[11] https://www.newspapers.com/image/390551860 [02/12/2022] Lloyd’s Weekly Newspaper published 13 December 1896

[12] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/61812 [02/12/2022] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; MEPO 6: Metropolitan Police: Criminal Record Office: Habitual Criminals Registers and Miscellaneous Papers; Reference: MEPO 6/12a

[13] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60861 {02/12/2022] . UK, Police Gazettes, 1812-1902, 1921-1927

[14] LMA reference (not online datail)

[15] London Metropolitan Archives; Bow Street Magistrates Court, Court Registers, Reference: PS/BOW/A/04/009

[16] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/61808 [02/12/2022] The National Archives; Kew, London, England; HO 140 Home Office: Calendar of Prisoners; Reference: HO 140/210

[17] https://www.findmypast.co.uk/transcript?id=GBOR/PLYCAT/WORK/521414 [02/12/202] Plymouth & West Devon Record Office; Devon,Plymouth & West Devon parish chest records 1556-1950

[18] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60895 [02/12/2022] Gloucestershire Archives; Gloucester, Gloucestershire, England; Reference: Q/Gc/12/17

[19] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/8914 [02/12/2022] General Register Office; England & Wales, Civil Registration Death Index, 1837-1915

[20] https://www.ancestry.co.uk/search/collections/60391 [02/12/2022] London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; London Workhouse Admission & Discharge Registers; Reference Number: HOBG/542/22

[21]https://www.independent.co.uk/news/uk/home-news/sleep-soundly-incorrigible-rogues-you-re-no-longer-committing-a-criminal-offence-9000162.html [ 21/11/2022] The Independent newspaper published 13 December 2013

[22]https://www.theguardian.com/society/2023/apr/02/thousands-of-homeless-people-arrested-under-archaic-vagrancy-act [02/04/2023] The Observer newspaper published 2 April 2023

[23]https://www.crisis.org.uk/about-us/the-crisis-blog/is-it-scrapped-yet-an-update-on-our-campaign-to-repeal-the-vagrancy-act/ Crisis.org Website [11/01/2023]