In Victorian London, not all “crimes of fashion” were actually fashionable.

By Summer Anne Lee

Such is the case when it comes to Bloomerism, an American women’s dress reform movement that spread to London in 1851. Join us on a journey through history to unravel the captivating story of Bloomerism as encountered by London police, and its lasting influence on women’s fashion and empowerment, as hosted on the Bow Street Police Museum blog.

ORIGINS OF BLOOMERISM

In the spring of 1851, an American woman named Elizabeth Smith Miller decided she had enough of cumbersome Victorian fashion. While working in her garden she became “disgusted” with her long skirt, which would have inevitably become caked with dirt as she tended to her plants.[1] At that moment, she suddenly decided that she was going to start wearing trousers.

Miller didn’t just simply start wearing men’s trousers. Her invention was inspired by depictions of Turkish dress, a culture in which both men and women wore voluminous bifurcated trousers known as şalvar. Over her new trousers, she wore a shortened dress that reached about four inches below the knee (Fig. 1). When Miller traveled to Seneca Falls, New York, her cousin (a famous suffragist) Elizabeth Stanton and her neighbor Amelia Bloomer adopted the trousers as well.

Bloomer publicized news of this costume in the April 1851 edition of her newspaper called The Lily, and before long the “Bloomer” costume spread all over the United States. By May of that year, women wrote to Bloomer asking for sewing instructions to make their own “Bloomer costume.”[2] One American suffragist and abolitionist, Hannah Tracy Cutler, wore bloomers when she attended the World’s Peace Congress in London that August, the same month the following was reported in the London-based publication Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine and Gazette of the Fashionable World:

“The new [Bloomer] costume now so much the rage among the ladies of the northern states of America has made no progress among the fair of Great Britain … A number of the leading papers in the United States predict that in six months’ time the new dress will be almost universally adopted, and they further call on every ‘sensible and self-thinking woman’ to consult her comfort, despite the clamour of narrow-minded fault-finders.”[3]

BLOOMERS IN LONDON

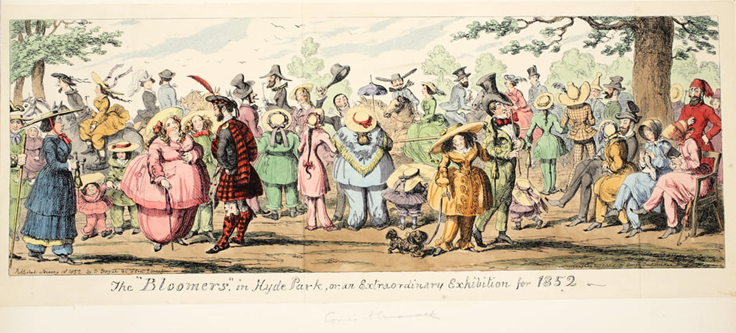

It was not long, however, that “Bloomerism” appeared in London as well (Fig. 2). And rest assured, the Bow Street Police were aware of it.

In September of 1851, the London Illustrated News reported how the residents of London’s Brompton Square were “astonished” by “three young and beautiful ladies … appearing in the full Bloomer costume.” The reporter also shared that two ladies in the “unusual costume”[4] appeared in the West End and passed out a number of handbills encouraging women and dressmakers to join the association of Bloomers founded near Fitzroy Square.

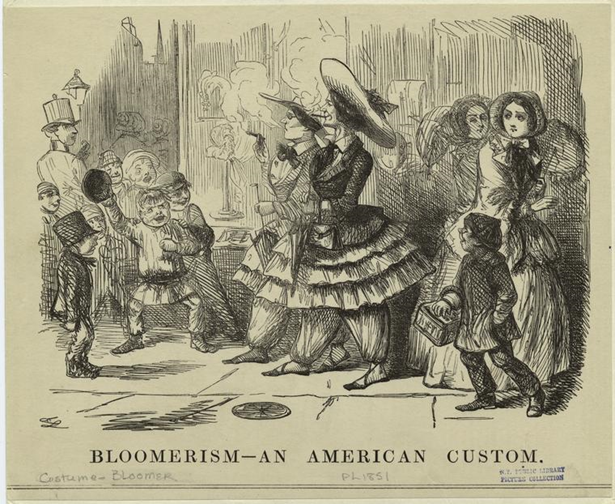

It wasn’t long before bloomers began to attract police attention. The next month, on October 26th, 1851, Reynolds’s Newspaper published an article titled “A Dexterous Bloomer.”[5] The report shared that three women dressed in feathered hats and bloomers (Fig. 3), referred to as a costume outre et ridicule,had too much to drink at a saloon on Marlborough Street the previous evening. One of the three, named Jane Watson, was described as wearing “a cloth tunic, white satin vest, and blue cloth ‘unmentionables’” — likely referencing how her bloomers looked like drawers, a ladies’ undergarment. The sight of these women leaving the bar apparently caused quite a scene, as they reportedly became surrounded by a crowd of “at least 100 persons.”

A fight ensued after a young woman dared to disagree with Watson, who was extolling the virtues of the bloomer costume. Watson reportedly “tore the skirts from her dress,” provoking a violent row in which Watson also allegedly punched the young woman, knocking her to the ground. At this point, a police officer came to arrest Watson — and the other two “‘Bloomers,’ unobstructed by long skirts, at the sight of the officer, darted off with the speed of a deer.”

Even five years later, it seems bloomers were still a spectacular sight in London (see Fig. 4).

Another report from Reynolds’s Newspaper, this time from 1856, shared another tale of “Three Bloomers in Trouble.”[6] The article shared that three girls all under the age of 18, named Jane Mordaunt, Harriet Davis, and Jannette Duval, “were charged with causing a disturbance and annoying the foot passengers in Regent-street.” At midnight on the 8th of August, the three girls, who admittedly had been drinking, were walking arm-in-arm, singing and pushing against other pedestrians. They were reportedly “surrounded by at least 300 persons, who seemed highly amused at their singular and indecent appearance.” The girls were arrested and fined 5 shillings each. The report concluded that when they left the court, “they ran away in the direction of Regent-street and followed by nearly a thousand persons.”

BLOOMER COSTUME TO BICYCLE COSTUME

It was precisely this extreme reaction to bloomerism that caused this movement to ultimately fail, including in the United States. American women who publicly wore bloomers throughout the 1850s were followed by crowds and were ridiculed, stared at, and shouted at in the streets. The harassment the costume brought upon not only themselves, but also their family members, forced most of these dress reformers to return to long skirts.

Why did people react so strongly to the sight of a woman in trousers? The bloomerism movement was greatly associated with the fight for women’s right to vote, presenting a challenge to the status quo. Satirical images of women wearing bloomers also showed them performing other mannish activities, like smoking, drinking alcohol, or even acting as policemen. At the time, many people believed that if women began dressing like men, they would also act like men — and in turn, men would act more like women. This was a problem because gender roles in the nineteenth century were very rigid.

Although most of the daring women who wore the bloomer costume in the 1850s abandoned it, bloomerism did find a more lasting legacy in women’s fashions for activities like swimming, cricketing, calisthenics, skating, and climbing. Divided skirts and bifurcated garments similar to bloomers became especially important as the popularity of bicycling grew in the late nineteenth century. In the 1880s a new dress reform movement, known as the Rational Dress Association, was especially enthusiastic about this new costume which allowed women to wear trousers in more socially acceptable ways.

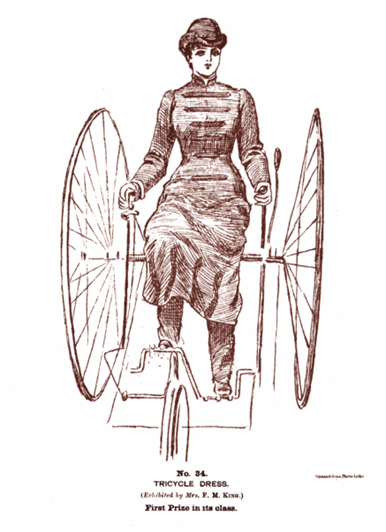

Figure 6. “Tricycle Dress,” published in The Exhibition of the Rational Dress Association …: Catalogue of Exhibits and List of Exhibitors, 1883.

This enthusiasm for trousers is apparent in the catalogue for the 1883 Exhibition of the Rational Dress Association held at Prince’s Hall in Piccadilly.[7] This catalogue featured many illustrations and descriptions of so-called “rational dress,” promoting women’s clothing that was more practical, comfortable, and hygienic than the leading fashions of the 1880s. Main features include the use of trousers and designs intended to be worn without a corset.

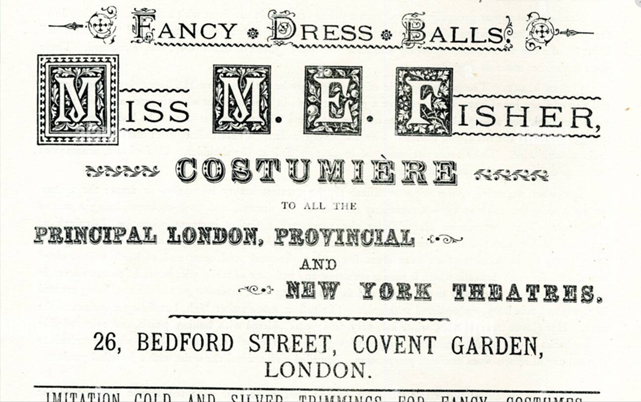

Among the exhibitors listed was M. E. Fisher, a costumière who worked out of 26 Bedford Street, Covent Garden — located less than one-third of a mile from where the Bow Street Police Museum is located today! Fisher was recorded as having exhibited all of the following ensembles:

- Lady’s Tricycle or Walking Dress (of the Future).

- Lady’s Boating Dress.

- Lady’s Lawn-tennis Dress.

- Lady’s Walking or Tricycle Dress.

- Turkish Dress.

- Greek Dress.

- Costume of “A Love-sick Maiden.” (Opera of “Patience.”)

In conclusion, although initially met with ridicule, the Bloomer costume symbolized a larger movement for women’s rights and gender equality in America and England. The arrival of the Bloomer costume in the summer of 1851 stirred curiosity and controversy highlighting public resistance to change. Although it was not illegal for women to wear Bloomers, their spectacular appearance caused crowds to gather around and follow women wearing Bloomers — attracting police attention. Although Bloomerism never exactly went mainstream, the spirit of reform lived on through London’s Rational Dress Association in the 1880s, which promoted practical and comfortable clothing for women, including trousers. And the evidence of M. E. Fisher’s participation in their 1883 exhibition proves that women’s dress reform spread to Covent Garden.

Bibliography

- Chrisman-Campbell, Kimberly. “When American Suffragists Tried to ‘Wear the Pants.’” The Atlantic, June 12, 2019. https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/06/american-suffragists-bloomers-pants-history/591484/.

- “Correspondence.” Lily. June 1851, volume 8, number 6 edition.

- “Last Week’s Latest News.” Reynolds’s Newspaper, 26 Oct. 1851. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/Y3200506938/BNCN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=ae769b8d. Accessed 28 July 2023.

- “Metropolitan News.” Illustrated London News, September 13, 1851, 330. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003 (accessed October 7, 2023). https://link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/HN3100029057/ILN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-ILN&xid=dc2fcff5.

- The Exhibition of the Rational Dress Association …: Catalogue of Exhibits and List of Exhibitors. London: Wyman, 1883.

- “The New Female Costume.” Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine and Gazette of the Fashionable World. August 1851.

- “Yesterday’s Law, Police, Etc.” Reynolds’s Newspaper, 10 Aug. 1856. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/Y3200518890/BNCN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=c125bf6b. Accessed 28 July 2023.

[1] Kimberly Chrisman-Campbell, “When American Suffragists Tried to ‘Wear the Pants,’” The Atlantic, June 12, 2019, https://www.theatlantic.com/entertainment/archive/2019/06/american-suffragists-bloomers-pants-history/591484/.

[2] “Correspondence,” Lily, June 1851, volume 8, number 6, page 47. https://rbscp.lib.rochester.edu/viewer/475

[3] “The New Female Costume.” Blackwood’s Lady’s Magazine and Gazette of the Fashionable World. August 1851, page 75. https://books.google.com/books?id=dEQFAAAAQAAJ&q=bloomer#v=snippet&q=bloomer&f=false

[4] “Metropolitan News.” Illustrated London News, September 13, 1851, 330. The Illustrated London News Historical Archive, 1842-2003 (accessed October 7, 2023). https://link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/HN3100029057/ILN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-ILN&xid=dc2fcff5.

[5] “Last Week’s Latest News.” Reynolds’s Newspaper, 26 Oct. 1851. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/Y3200506938/BNCN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=ae769b8d. Accessed 28 July 2023.

[6] “Yesterday’s Law, Police, Etc.” Reynolds’s Newspaper, 10 Aug. 1856. British Library Newspapers, link-gale-com.i.ezproxy.nypl.org/apps/doc/Y3200518890/BNCN?u=nypl&sid=bookmark-BNCN&xid=c125bf6b. Accessed 28 July 2023.

[7] The Exhibition of the Rational Dress Association …: Catalogue of Exhibits and List of Exhibitors (London: Wyman, 1883). https://books.google.com/books?id=hj8CAAAAQAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&printsec=frontcover#v=onepage&q&f=false