By Jon S

Boxing has always divided opinion on whether it is a demonstration of physical discipline or simple brutal violence and the legality of some contests put on for entertainment purposes was questionable.

By the late 1800s attempts were being made to draw a clear distinction between contests put on for the demonstration of the sporting art that could be considered legal as opposed to the no-holds-barred prize fighting that drew a rowdy audience enticed by the violence, drinking and side betting.

Various bodies drew up a series of regulations designed to ensure greater control of the contests and it was those that were drawn up by the Amateur Athletic Club that became the accepted standard, introducing the use of gloves; 3 minute rounds; breaks between rounds; the 10 second count; weight divisions; along with other measures.

Due to his love of boxing, and patronage of the Amateur Athletic Club, these rules were named after the 9th Marquess of Queensberry and “Queensberry Rules” has become a byword for decent and fair behaviour. Queensberry himself did not fit this description, known for being cantankerous and bullying as evidenced by his role in triggering the Oscar Wilde affair.

At the forefront of promoting the respectability of boxing was the National Sporting Club (NSC). A private members club established in 1891 by co-managers John Fleming and Arthur Bettinson, with the Earl of Lonsdale as its president. The club moved into one of the grand houses of the Covent Garden Piazza at 43 King Street.

A regular programme of boxing events, especially on Mondays, was put on and after dinner up to 1,300 members and their guests could make their way to the theatre to watch the bouts, contested under a slightly modified version of the Queensberry Rules. Reinforcing the message that the contests were a demonstration of skill and athleticism the audience were to remain silent at ringside, and smoking was not permitted.

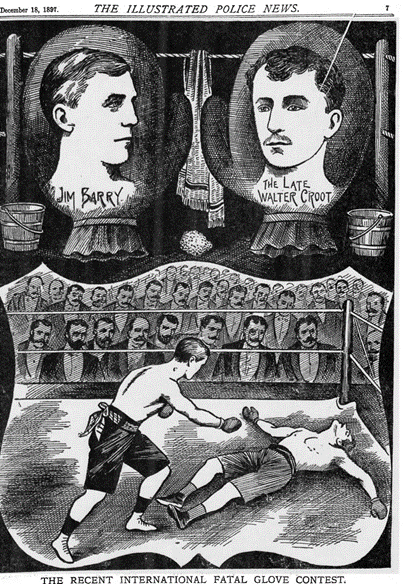

The club proved to be very successful and influential, becoming the de facto governing body for the sport in the UK with the best boxers from around the world travelling to compete in contests that would be considered as determining the champion of the world. In 1897 one of these bouts resulted in what is now considered the first championship boxing fatality, and the legality and morality of the sport brought into question once again. Jim Barry of Chicago was due to fight Walter Croot of Leytonstone on 16th November[1] at a 7st10 weight division (108lbs 49kg) but misfortune struck the club on the 15th November when John Fleming died of natural causes on the premises resulting in the club closing for two weeks and leaving Arthur Bettinson to take the reins as sole manager.[2]

The contest eventually took place on Monday 6th December over 20 three minute rounds commencing shortly before 11pm. With only seconds of the last round remaining Croot was knocked down and carried to the dressing room but never regained consciousness and passed away in the early hours of Tuesday morning.[3] On hearing the news at Bow Street, Inspector French visited the club at 9:30am to view the deceased’s body and met Arthur Bettinson. Telegrams were issued for other protagonists to return to the club and in the afternoon Detective Sergeant Croston brought in six people to appear before the magistrate Sir James Vaughan.

Jim Barry; Tom White (Barry’s second); William Watley (Croot’s second); Bernard Angle (Referee); Richard Smith (Timekeeper) and Arthur Bettinson were charged that “Between 10:50pm on 6th and 12:15am on 7th December concerned together with the manslaughter of Walter Croot during a boxing competition at the National Sporting Club”[4]

Vaughan bailed the accused on sureties of £50 per person and the case deferred for one week pending the outcome of the inquest, which was held at St Clements Danes Vestry Hall and returned a verdict of accidental death.[5] On 14th December Vaughan extended the bail for a further week as there had been no counsel for the prosecution.[6] One week later prosecution counsel advised that the Director of Public Prosecutions considered that there was no case to answer and a jury would not convict on a charge of manslaughter. With this direction Sir James Vaughan discharged the prisoners, to applause in the court, stating that boxing was “a good old English pastime which ought to be applauded”. He also added the observation that authorities should be given notice of the contests so that independent witnesses could be in attendance.[7]

Oddly, this meant that Bow Street officers would attend the club around 9pm on any boxing night and issue a warning to the officials and competitors before the programme commenced, but Police regulations did not allow for them to remain on site.

On 7th November 1898 Tom Turner of Holborn collapsed after his defeat to Nathaniel Smith of Paddington and was taken unconscious to Charing Cross Hospital where he was pronounced dead in the early hours of 10th November. Inspector Pardo, who had issued the caution, arranged for the arrest warrants for Bettinson, Smith, Bernard Angle (referee), Eugene Corri (timekeeper), Arthur Gutteridge (Turner’s second) and Barney Shepherd (Smith’s second). All bar Shepherd were charged with manslaughter before Sir John Bridge in the afternoon, and were bailed for one week on sureties of £50 pending the inquest.[8]

The inquest found that Turner suffered from a weak heart and recorded a verdict of Accidental Death. Returning to Bow Street on 17th November, with Barney Shepherd now added to the defendants, Sir John Bridge committed the charge to trial to the Old Bailey. In summing up Bridge stated “it was necessary and right that young men should become experts in boxing as well as other manly exercises’ and referenced the risks involved in other activities such as horse racing and cricket but was concerned that this contest may not have been a demonstration of artistic skill but an illegal prize fight.[9]

On 22nd November at the Central Criminal Court, the Recorder of London Sir Charles Hall instructed that there was no case to answer,[10] and the Grand Jury (a group that assessed whether the case should proceed in front of a trial jury) threw out the charge accordingly.[11] After a few weeks of closure boxing recommenced at the NSC on 28th November with the main event being the Glaswegian Mike Riley’s victory over Charlie Exall of Bermondsey.[12]

On 29th January 1900 Riley was back in the Covent Garden ring against Matt Precious from Birmingham in a 15 round contest but he failed to leave his corner at the the start of the 10th and was taken to Charing Cross Hospital where he passed away at 8:45am the following morning. Once again warrants were issued; Inspector Bowles, having given the caution, arranged for the arrest and appearance of nine people before Albert de Rutzen in the afternoon of 30th January on the charge of “Manslaughter of Michael Reilly (sic) at the National Sporting Club”.[13]

There were multiple appearances and delays at the magistrates court over the next two weeks as De Rutzen requested legal representation for the police, that had not been needed before; the defence counsel was unavailable and other cases hindered the time available for this to be heard. As before, all of the accused, which numbered ten by 2nd February, were bailed on £50 sureties. In the interim the inquest had returned a verdict of accidental death noting that the NSC had taken every possible safety precaution.[14]

On 21st February De Rutzen finally delivered his verdict that it was beyond the role of a magistrate to determine but needed a jury decision. Bail was raised to £100 and Bettinson, Precious, Bernard Angle (Referee), Richard Smith (Timekeeper) and six people acting as seconds – William Gee, Harry James, John Boyle, Walter Eyles, John McShane and Anthony Diamond awaited trial at the Old Bailey.[15]

At the opening of the sessions on 12th March the Grand Jury dismissed the charge.[16]

Yet again, similar events played out just over a year later when on Monday 22nd April 1901 British born Murray Livingstone who had settled in America and fought under the name Billy Smith took on Jack Roberts of Drury Lane. Smith collapsed at the end of the 8th round and was taken to Charing Cross Hospital but did not regain consciousness and died at 11:45 am on 24th April.[17]

On hearing of the deaths Bettinson and Roberts and the others who had been cautioned by Inspector Alfred Boxhall; J Herbert Douglas (Referee), Eugene Corri (Timekeeper) and the various seconds – William Chester, Arthur Gutteridge, Arthur Locke, William Baxter, Ben Jordan, Harry Greenfield handed themselves in at Bow Street in anticipation of the warrants and were duly charged in front of Albert De Rutzen that they “Did feloniously kill and slay Billy Smith at the National Sporting Club on 22 April 1901”.[18]

De Rutzen issued the usual one week’s remand with bail set at £100 pending the inquest which duly recorded a verdict of accidental death.[19] On the return to Bow Street on 2nd May Sir Franklin Lushington echoed the views of Sir John Bridge previously that an illegal prize fight may have taken place and committed the case to the old Bailey.[20]

On 13th May 1901 The Grand Jury accepted that this time there was a case to be heard,[21] and the trial was held two days later. However the jury was unable to reach a verdict resulting in the case being dismissed and retrial ordered.[22]

The retrial took place on 28th June with Charles Frederick Gill KC leading the defence team,[23] perhaps via association with the Marquess of Queensberry as Gill had prosecuted Oscar Wilde in 1895, and calling on prominent members of the club, most notably Lord Lonsdale but also Lord Kingston and Admiral Victor Montagu as witnesses. A guilty outcome would have had major consequences with the possibility of the sport being outlawed completely but all defendants were acquitted following the not guilty verdict,[24] and no further manslaughter cases have been brought in the uk following a fatality in the ring

The club had staged around 2,000 contests without incident between 1891 and 1897 but the deaths and legal cases over the subsequent 4 years reopened a wider debate on the worthiness of the sport irrespective of the legal precedent, with newspaper opinions,[25]and questions in the House of Commons arguing for the NSC to be shut down.[26]

Unsurprisingly Arthur Bettinson took a dim view of opponents, writing in his 1901 publication “An outcry was raised by everybody who was not present …… A sect of people who are never happy unless they are hysterical”.[27]

Each judicial vindication was welcomed as a victory for common sense but he did also regard the police with some contempt and objected to being “treated as a felon”. In his words again, “The people who are ‘wanted’ ….. are not hiding under beds or scaling slate roofs ……. they are waiting quietly in the Club for the officials who they themselves have sent for ……. and are collectively charged with the heinous crime of Manslaughter …. and marched off to Bow Street”.[28]

One further fatality occurred at the National Sporting Club in June 1916 when Louis Hood died after a contest with Charlie Hardcastle. Bettinson, Hardcastle, J Herbert Douglas (Referee), Eduardo Zeraga (Timekeeper), John Goodwin (Hardcastle’s second) and Jabez White (Hood’s second) were arrested and remanded in the usual fashion; the inquest ruled death by misadventure but confirmation was received from the Public Prosecutor that no action was be to taken enabling the case to be discharged on 4th July.[29]

Despite the opposition, with legal respectability came increased popularity; many new smaller venues were used around the country and new promoters sought larger arenas such as the 10,000 capacity Olympia Exhibition Centre in Kensington for the headline contests.[30] Then, in 1924, the first contest took place at the recently opened Wembley Stadium.[31]

By the late 1920s the influence of the NSC had dwindled with the British Boxing board of Control (BBBC) being established in 1929 as the official governing body of the sport,[32] Lord Lonsdale and JH Douglas taking prominent positions, Arthur Bettinson having died in 1926.

The club vacated 43 King Street and Covent Garden’s place at the forefront of boxing was over. The debate on whether it is a noble art or barbaric sport continues.

Additional Notes:

The son of JH Douglas, JWHT Douglas won the gold medal for boxing at the 1908 Olympics and went on to captain Essex and England at cricket; both father and son drowned in a shipping collision 1930.[33]

Arthur Gutteridge’s grandson Reg would become a household name as ITV’s boxing commentator from the 1960s to the 1990s in a period when the main bouts received prime time television coverage.[34]

The Tragic Victims:

Walter Croot – Age 22 weight division 7st 8 (weighed in 7st 6)

Tom Turner – Age 23 weight division 8st 8

Mike Riley – Age 19 weight division 7st 8 (weighed in 7st 6)

Billy Smith – Age 25 weight division 9st

Louis Hood – Age 18 weight division c.9st (private war meet – official weights not taken)

References:

The National Sporting Club Past and Present; by AF Bettinson & W Outram Tristram published 1901 – BLL UIN 01000306267

Noble and Many: The History of the National Sporting Club by Guy Deghy published 1956 – BLL UIN 01000893984

[1] https://www.newspapers.com [27/04/2023]; The Buffalo Times (Buffalo, New York) 30 Nov 1897

[2] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; Evening Standard (London, Greater London, England) · 15 Nov 1897

[3] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; Daily Telegraph 8 Dec 1897

[4] London Metropolitan Archives; Bow Street Magistrates Court, Court Registers, Reference: PS/BOW/A/01/005

[5] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; The Evening Standard 11 Dec 1897

[6] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; The Times 15 Dec 1897

[7] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; The Standard 22 Dec 1897

[8] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; Evening Standard 10 Nov 1898

[9] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023]; The Guardian 18 Nov 1898

[10] https://www.newspapers.com [05/04/2023]; Evening Standard 21 Nov 1898

[11] https://www.newspapers.com [05/04/2023]; The Guardian 23 Nov 1898

[12] https://www.newspapers.com [27/04/2023] The Pall Mall Gazette 29 Nov 1898

[13] London Metropolitan Archives; Bow Street Magistrates Court, Court Registers, Reference: PS/BOW/A/01/010

[14] https://www.newspapers.com [04/04/2023] The Daily Telegraph 3 Feb 1900

[15] https://www.newspapers.com [05/04/2023] The Standard 22 Feb 1900

[16] https://www.newspapers.com [05/4/2023] The Standard 13 Mar 1900

[17] https://www.newspapers.com [12/04/2023] Evening Standard 24 Apr 1901

[18] London Metropolitan Archives; Bow Street Magistrates Court, Court Registers, Reference: PS/BOW/A/01/014

[19] https://www.newspapers.com [15/05/2023] Evening Standard 29 Apr 1901

[20] https://www.newspapers.com [12/04/2023] Evening Standard 2 May 1901

[21] https://www.newspapers.com [05/04/2023] Evening Standard 13 May 1901

[22] https://www.newspapers.com [15/05/2023] Evening Standard 15 May 1901

[23] Old Bailey Proceedings Online (www.oldbaileyonline.org, version 8.0, 31 May 2023), June 1901, trial of JACK ROBERTS ARTHUR FREDERICK BETTINSON JOHN HERBERT DOUGLAS EUGENE CORRI ARTHUR GUTTERIDGE ARTHUR LOCK WILLIAM CHESTER WILLIAM BAXTER BENJAMIN JORDAN HARRY GREENFIELD, (t19010624-479).

[24] https://www.newspapers.com [05/04/2023] The Times 29 Jun 1901

[25] https://www,newspapers.com [04/04/2023 Daily News 8 Dec 1897

[26]https://api.parliament.uk/historic-hansard/commons/1901/may/02/boxing-fatality-at-the-national-sporting#S4V0093P0_19010502_HOC_209

[27] The National Sporting Club Past & Present, 1901 pp88

[28] The National Sporting Club Past & Present, 1901 pp146-147

[29] https://www.newspapers.com [06/04/2023] Manchester Evening News 4 Jul 1916

[30] https://www.newspapers.com [16/05/2023] The Guardian 18 Jun 1919

[31] https://www.newspapers.com [16/05/2023] The People 10 Aug 1924

[32] https://www.newspapers.com [16/05/2023] The Guardian 22 Dec 1928

[33] https://www.espncricinfo.com/cricketers/johnny-douglas-11927

[34] https://www.theguardian.com/media/2009/jan/27/obituary-boxing-reg-gutteridge-television