A look at Bow Street’s early efforts against illegal gambling

Written by Su-Lian Ho

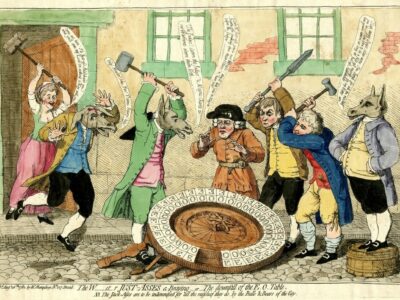

“The W—st—r Just-Asses a-braying”, James Gillray, 1782. Source: British Museum.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_J-4-69

What does this 18th century satirical cartoon have to do with Bow Street? The image, by the famous satirist James Gillray, portrays a raid on an illegal gambling house – but the law enforcers have ass’s heads and are described as “Just-Asses” (a pun on “justices”[1]). It seems not everyone was a fan of their work: a common hazard of policing, perhaps!

When Henry Fielding began to build the Bow Street force, he focused on serious crimes like highway robbery. But when his brother John Fielding took charge in 1754, he was also expected to deal with societal problems like drunkenness and gambling (or “gaming”). This reflected a growing belief in English society that such activities “encouraged laziness and bad habits, that led inevitably to bad companions and bad life choices”.[2] In effect, it was an early form of preventive policing.

This was in tune with John’s own views. He was already a member of several charities dealing with poverty, prostitution and homelessness. In 1758, he wrote that he wanted to eliminate “disorders” such as gaming, begging, prostitution and “illegal music” and dances[3] (perhaps the 18th century version of a rave?). In 1761, he argued that gaming was closely linked with fraud and deceit.[4]

One activity that caught Fielding’s attention was the increasingly popular game of EO (Evens and Odds), an early form of roulette. Records show that in 1758, Fielding paid a ten guinea reward (over £1000 today) to one of his men for destroying two EO tables. These raids were unpopular with some of the public, who obviously felt that Fielding was a spoilsport, so he sometimes had to hire guards to keep the peace while the raids were performed.[5]

As the Gillray cartoon illustrates, the raids continued under Fielding’s successor Sampson Wright who took over in 1780. He was equally determined to target the gaming houses[6] and was said to have a particular dislike of EO.[7] The cartoon, reportedly based on a real-life raid, shows an EO table being smashed by a group of men led by Bow Street justices William Addington (referred to as “Addlehead”) and Wright (“Wright” with the W crossed out). To the side with hands in his pockets is their clerk Mr Bond.[8] Addington shouts for help while being hit over the head by a woman with a broom. A man warns the justices that their actions are improper (“You’re not Wright!”) but Bond confidently urges them on.

The cartoon depicts the Bow Street justices as foolishly over-enthusiastic and possibly acting beyond their remit. Mr Wright even says: “damn the Judges! & Magna Charta too!”. It is worth noting that a bill to outlaw EO was rejected by Parliament that same year.[9] The caption further alleges that the “Just-Asses” were backed by City bankers (“Bulls and Bears of the City”), likely referring to a report that a group of bank directors had begged the Home Secretary to extend the gaming laws.[10] If true, then this probably made the raids even less popular amongst typical Londoners. It must be remembered, of course, that Gillray was exaggerating events for satirical effect.

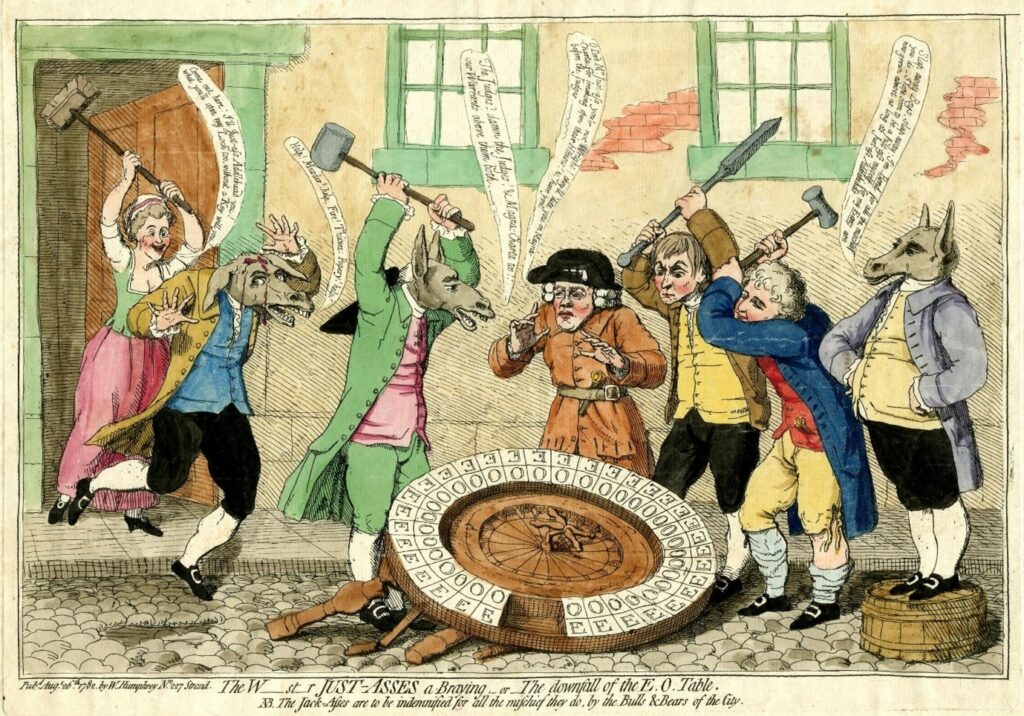

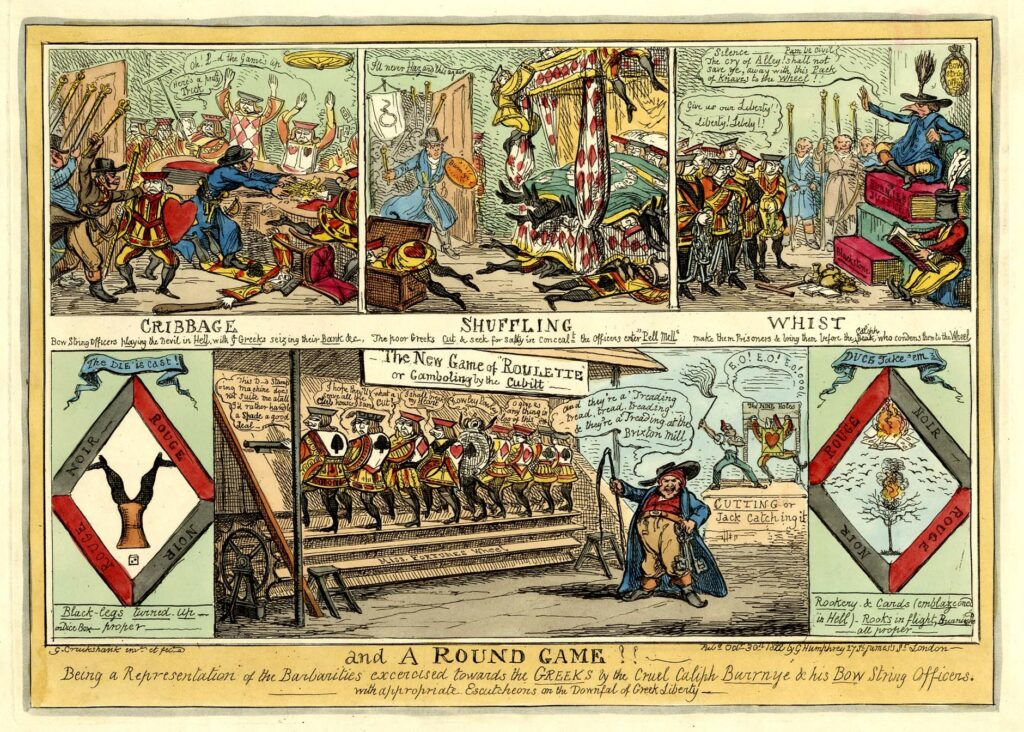

Bow Street’s fight against illegal gambling carried on into the next century, still unpopular amongst some, and still providing material for cartoonists like George Cruikshank (below). By then, the initiative was led by Richard Birnie, the new head at Bow Street (described as “Cruel Caliph Burrnye and his Bow String officers”), and EO had given way to “the New Game of Roulette”. Those found guilty could be sentenced to hard labour, walking on something called the Treadmill for hours on end (see lower half of image).

Cribbage, Shuffling, Whist and a Round Game” George Cruikshank, 1822. Source: British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1859-0316-172

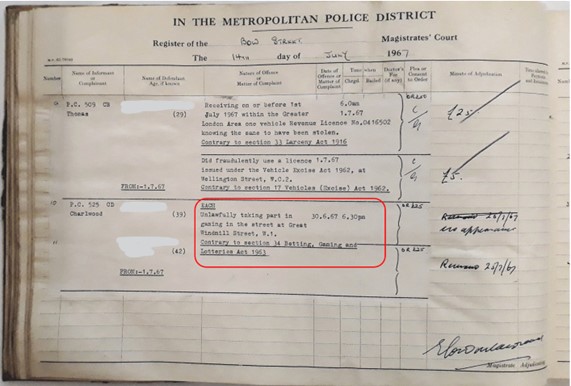

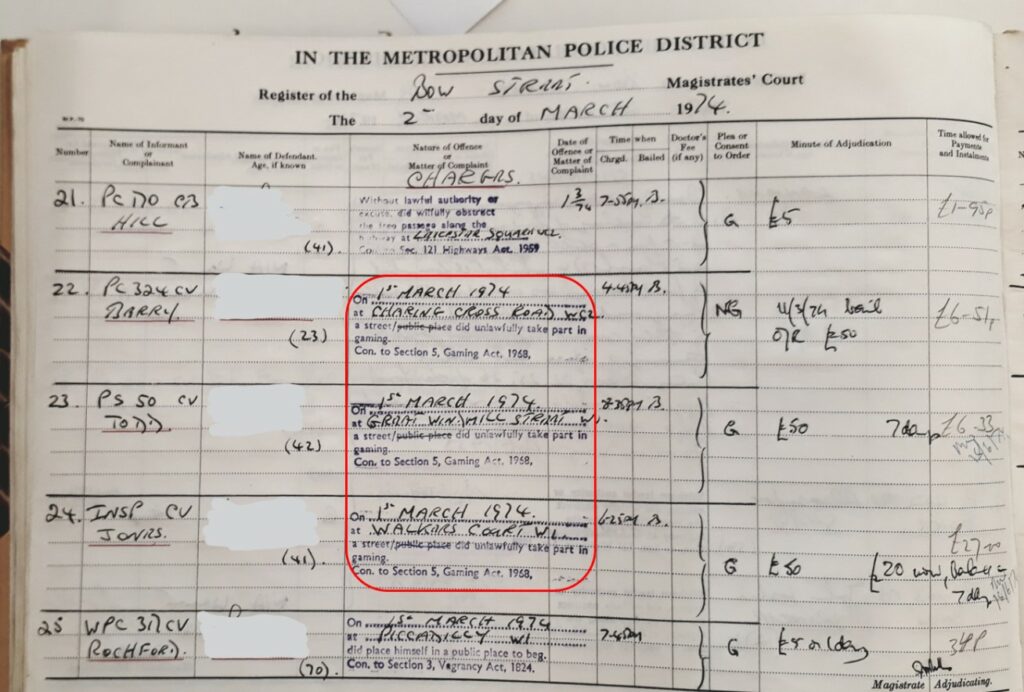

Gaming laws were amalgamated into the Gaming Act 1845, which (among other things) allowed law enforcers to use force to enter premises where “unlawful Games” were held, even “breaking open Doors” if necessary.[11] These laws evolved over time, as seen in late 20th century entries in the Bow Street Magistrates Court register (below). In the first, dated July 1967, a person is charged with illegal gaming under the Betting, Gaming & Lotteries Act 1963, while the entries dated March 1974 refer to the Gaming Act 1968. It seems the gamblers were usually let off with a fine, arguably a more realistic and humane way of dealing with the issue. Not such spoilsports any more!

Source: London Metropolitan Archives

Bibliography

Beattie, J. M. (2012), The first English detectives: the Bow Street Runners and the policing of London, 1750-1840. Oxford: Oxford University Press

Gaming Act 1845, https://www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/Vict/8-9/109/enacted/data.pdf (accessed on 14 Sept 2022)

George, M. Dorothy (1952). Catalogue of political and personal satires preserved in the Department of Prints and Drawings in the British Museum. London: British Museum

Kennison, P. and Cook, A., (2019). Policing from Bow Street: Principal Officers, Runners and The Patroles. London: Blue Lamp Books

[1] Gaming Act 1845, Section III

[1] An alternative term for “magistrates”

[2] Beattie, 2012, p42

[3] Beattie, 2012, p44

[4] Beattie, 2012, p43, footnote 76

[5] Beattie, 2012, p45, footnote 86.

[6] Beattie, 2012, p196

[7] Kennison & Cook, 2019, p64

[8] George, 1952, p647

[9] Beattie, 2012, p196

[10] London Chronicle, August 1782, as described in George, 1952, p648

[11] Gaming Act 1845, Section III