But where are they?

Written by Su-Lian Ho

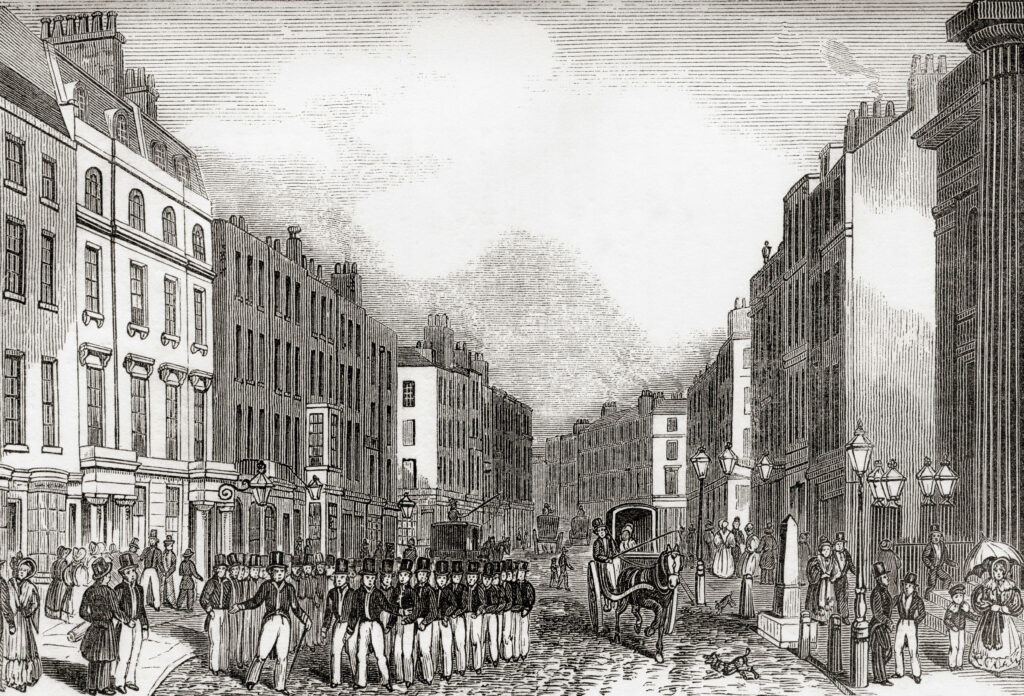

Many visitors to the Museum have heard of the Bow Street Runners, the popular name of the police force set up by Henry Fielding in 1749. This is usually because the name has appeared in a book or film. But when one delves more deeply, it is surprisingly difficult to find the Runners (properly known as Principal Officers) in major works of fiction, and even when they do appear they tend to be insignificant.

Fielding himself was a noted novelist who published his most famous work Tom Jones in the same year he founded the Bow Street force. Novels were a new-ish form of literature then, dismissed by scholars as light-weight and unimportant. As late as 1803, Jane Austen still joked about the embarrassment of being caught reading “only a novel”.[1]

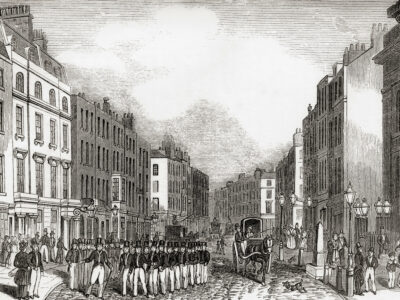

It was not until the rise of the detective novel in the early 19th century that the Runners gained more literary attention. David J Cox[2] cites two examples: Richmond: Scenes in the Life of a Bow Street Runner (published anonymously in 1827) and Delaware or The Ruined Family (1833) by G P R James. The first is a semi-fictional account of cases solved by a supposed real-life Bow Street officer, which Cox admits are of “limited literary merit”. Delaware is not much more readable, by Cox’s account, but it was the first novel to feature Bow Street Runners as important characters. James not only invents a clever Bow Street detective named Cousins but also incorporates a real-life Runner named George Ruthven in the story. Ruthven made his name as one of the Runners who helped foil the infamous Cato Street Conspiracy in 1820.

Few people today have heard of Richmond or Delaware, but they will have heard of Charles Dickens. Unfortunately, Dickens did not have a high opinion of the Runners, dismissing them as “men of very indifferent character” who were “utterly ineffective”.[3] He only mentions them in two novels. In Oliver Twist (1837), two Bow Street officers, satirically named Blathers and Duff,[4] are portrayed as officious and self-important. True to his name, Mr Blathers tells a long-winded story about a previous arrest: it takes up 700 words, which Dickens puts in one huge paragraph to suggest the boredom that the listeners must have felt.[5]

Bow Street men appear again in Great Expectations (1860) to investigate an attack on Mrs Gargery, Pip’s sister. Pip is unimpressed:

“The Constables and the Bow Street men from London – for this happened in the days of the extinct red-waistcoated police – were about the house for a week or two, and did pretty much what I have heard and read of like authorities doing in other such cases. They took up several obviously wrong people, and they ran their heads very hard against wrong ideas, and persisted in trying to fit the circumstances to the ideas, instead of trying to extract ideas from the circumstances. Also, they stood about the door of the Jolly Bargemen, with knowing and reserved looks that filled the whole neighbourhood with admiration; and they had a mysterious manner of taking their drink, that was almost as good as taking the culprit. But not quite, for they never did it.”[6]

As noted by Dickens, the Bow Street Runners no longer existed by the mid-1800s, having been merged into a wider metropolitan force some years after the Police Act 1829. Nonetheless, the name “Bow Street”, with its busy magistrate’s court and adjoining police station, remained a by-word for law enforcement. For example, in the Sherlock Holmes story The Man with the Twisted Lip, Dr John Watson says: “…we crossed over the river, and dashing up Wellington Street wheeled sharply to the right and found ourselves in Bow Street. Sherlock Holmes was well known to the force, and the two constables at the door saluted him.”[7] It was unnecessary to explain that “Bow Street” meant a police station.

So how can we explain the familiarity of the term “Bow Street Runners”? Some believe mistakenly that they appeared in the Sherlock Holmes series but though Bow Street was still synonymous with policing, the Runners had long ceased to exist when the first Holmes stories appeared in the 1880s. Holmes employed a band of street kids called the Baker Street Irregulars, which might be confused with the Runners.

The answer seems to be that the Runners have been enshrined in all sorts of popular entertainment over the years. They figured prominently in the film Carry On Dick (1974), played by comic actors Bernard Bresslaw, Kenneth Williams and Jack Douglas. They feature regularly in Regency period[8] romantic novels, where their fate has been mixed: in Georgette Heyer’s stories they are rough and bumbling but in Lisa Kleypas’ books they are hunky romantic heroes! They have appeared in various historical TV series, including the well-regarded City of Vice (2008), as well as Netflix’s Bridgerton (2020) where they are tasked with finding the scandalous society author Lady Whistledown.

Clearly, not all of these are works of high art or literature but the Runners probably would not have cared. They were men of the people, not high intellectuals: some were even ex-criminals. To be remembered over 200 years after their demise would be worth a bit of sneering by Dickens.

Do you remember where you first heard of the Bow Street Runners? Let us know!

Bibliography

Austen, J (1803), Northanger Abbey, Chapter V

Conan Doyle, A (1891), “The Man with the Twisted Lip”, first published in The Strand magazine, December 1891

Cox, David J (2016), “The Bow Street Runners in Fact and Fictional Narrative”, Chapter 7, Law, Crime and Deviance since 1700, ed. Anne-Marie Kilday and David Nash (Bloomsbury)

Dickens, C. (1837), Oliver Twist, Chapter XXXI

Dickens, C (1860), Great Expectations, Chapter XVI

[1] Austen, J. (1803), Northanger Abbey, Chapter V

[2] Cox, David J (2016), “The Bow Street Runners in Fact and Fictional Narrative”, Chapter 7, Law, Crime and Deviance since 1700, ed. Anne-Marie Kilday and David Nash (Bloomsbury).

[3] Dickens, C. (1850), “A Detective Police-Party”, in Household Words, Vol I No 18, 27 July 1850, as quoted by Cox (2016).

[4] “Blather”: to talk foolishly at length. “Duff”: may mean 1) a pudding, 2) buttocks or 3) inferior. Source: Merriam-Webster.com

[5] Dickens, C. (1837), Oliver Twist, Chapter XXXI

[6] Dickens, C. (1860), Great Expectations, Chapter XVI

[7] Conan Doyle, A. (1891), “The Man with the Twisted Lip”, first published in The Strand magazine, December 1891

[8] Late 18th century to 1837